So, it’s been a year. This header won’t attempt to offer another summary of these “uncertain times”, but it will attempt to explain how it affected what we watched. With theaters shuttered, filming halted, foreign imports stalled, and blockbusters punted to weekends beyond, a looming entertainment vacuum defined most of this year. Let’s call 2020 a rebuilding year.

While a lot of the year’s release calendar resembled a take-out-the-trash-to-VOD fire sale, it offered greater focus on the important role bad films fulfill: in biding time, eliciting guffaws, and serving as a benchmark from which to compare to great films. Elsewhere, films that serendipitously played with horror and isolation seized a zeitgeist. And even few smaller films (and marginalized directorial voices) benefitted from an unoccupied spotlight to really shine (let’s say they had a “sourdough moment”).

While tracking down lauded awards contenders became a fun sport of managing PVOD drops, illicitly traded screeners, and sojourns to drive-ins far away, some major releases were relegated to becoming pawns in the mad-scramble taming of the wild west of streaming apps.

And while lockdown certainly gave me more time to watch, it did take its toll on me creatively. It turns out my extroverted nature excels at writing when I’m out in the world, juggling concentration with a spitting espresso machine or the habitual jerk of the 217 Metro bus. So, while the following may not be my plague-born King Lear, it serves as a continuation of the work of my late friend, Hunter Lurie, and his annual Filmography project.

Culled from 130+ 2020 American theatrical releases (factoring in its ever-expanding and contracting definition) I saw this year, as always I’ve given ample consideration given to both the high and the low, the popcorn and the art house, and the good and the just plain bad.

So as you commute from bedroom to kitchen, take in a read apart from the doomscrolling or at least click the thumbnails to be treated to trailers for the films you may have missed during our long slide into 2021. Enjoy!

The films that never found their audience, could just use some more exposure, or deserve another look.

Included on this list simply for being one of the best-looking films of the year, full stop. A small film with grand, widescreen scale, the landscapes that scale down our main character, Ulises, and make him so minute are something to behold. A tale of two cities–Monterrey in the rearview mirror, and an alien New York City brooding–is linked by a chugging cumbia beat. While its narrative dances a familiar routine, it’s commendable that it resists all temptation of wrapping everything up in a nice, saccharine bow.

A first-of-its-kind experiment in creating a narrative film for the International Olympic Committee’s artist-in-residence program, Olympic Dreams is a small, sweet romcom captured during the PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Winter Games. The setting inevitably allows for cinema verite moments of dramatic beats being interrupted by actual passers-by asking for directions, but it also helps contextualize the lead characters’ relationship. Here is a tight two weeks when someone who’s sacrificed their entire life in pursuit of a single aim can careen into an aimless mid-life crisis at the intersection of the world and just go for it.

First-time director Dave Franco makes his first priority here nailing the first-act hangout routine of our protagonists. Their banter and interplay alone is hook enough for a middle-of-the-road mumblecore success, but when The Rental transforms into a home invasion thriller for the AirBnb generation, their personal drama unwinds at a brisk and entertaining clip. Light yet knotty, the perfect *ahem* rental for fans of Drew Goddard.

There’s nothing like watching someone work through their demons in real time to encourage you to examine your own. The patient here is late-career Abel Ferrara, who has taken his real-life wife and daughter in their home apartment and paired them against his addict artist avatar, a career-best Willem Dafoe. It can hopscotch into some pretty dark places, but ultimately its loose, almost zen stillness makes this a transcendent therapeutic experience.

A caper that’s incredibly light on its feet, The Whistlers has very little substance, but more than enough style to make up for it. The requisite elements are all here: stashed cash, wire taps, double crosses, and a fresh-faced femme fatale. What elevates this above the dumping ground of a Netflix genre slate is a Michael-Mann-level of focus on the process behind mastering a single skill. Thankfully, instead of watching someone practicing safecracking in a dim room, we’re treated to spacious oceanfront backyards, quiet morning cityscapes, and sports cars winding up roads to picturesque overlooks in effort for characters to learn a coded whistling language. Needlessly fun, its weirdness is buoyed by stipples of black humor.

This is probably the most subjective category in this rollup. While my internal log dedicates this award in years past to high-fiving strangers at the end of the cold open race in The Fate of the Furious or the oblivious octogenarian who, from the front-row of a sold-out screening, called every fight in The Raid 2 aloud like a boxing commentator, this space is also reserved for Hilarious Disasters in Moviegoing. My first viewing of Tenet was one of these.

In the country’s second-largest theater market, for much of the year, the only way to see the trickle of films that braved to be “in theaters” was to scour the Southland for the few drive-ins pumping in new titles. Thankfully, after resisting the urge to make the trip down to a drive-in in San Diego, Paramount Drive-In Threatres at the end of Los Angeles County line decided to buy in a few weeks after Tenet officially premiered.

After extensive online research, my friends and I produced a socially-distanced three-car caravan and arrived an hour-plus early to wait in a parking lot outside the ticket queue. As the booths opened up, 50 cars commenced in bottleneck running of the bulls, jockeying for front. Through some conference calling and creative cutting, my friends and I were able to secure three contiguous spots not too far from the screen. Of course, as the film started to roll, the real struggle began.

No matter how loud we turned our radios up, Christopher Nolan’s famously inhuman sense of sound and audio mixing made confusing dialogue straight-up indecipherable. Of course, even if it was clear, it’d be competing against the frequent rumbles and air horns of passing freight trains from neighboring tracks (a staple of every Los Angeles drive-in). By the time the largest earthquake the city had experienced all year (with a noteworthy 4.6 magnitude) rolled in to shake everyone’s cars, our dulled senses could barely comprehend it.

When the credits rolled and my masked friends and I proceeded to shout across car windows to compare summaries of what just happened, we realized we were just as lost as the film’s Protagonist. Maybe we saw Tenet the way it really was meant to be seen: don’t try to understand it, just feel it.

What’s the (probably) Dutch word for missing something you never knew you loved? That sensation is tickled every few minutes for the smallest details during Small Axe: Lovers Rock. In our indefinite lockdown, bouncers whose gaze you’ll never catch are out of work and the sticky layers of dance floors are gathering dust. But here, in this anonymous London flat on an otherwise unremarkable night in 1980, they’re coronated as integral elements of the perfect social gathering.

Usually characters coming out of their shells by unnaturally jumping up and down in slow motion to a pop song at a house party elicits a cringe. The same trope occurs here, but when it’s flanked by the down moments of bathroom lines, patrons grabbing the wrong drink cups off a speaker, and walls sweating, it earns its moment.

While we haven’t been able to go out in pursuit of the ever-elusive best night of our lives, Small Axe: Lovers Rock gave us a private dance and something to look forward to: when the eventual post-vaccination 2021 reunion ragers commence, the real ones will congregate on the floor to sing Janet Kay’s “Silly Games” a capella. Everyone else can go home.

It’s difficult to figure out who deserves the blame for this one. While the oppressive blacks and browns of Zack Snyder’s DC mandate are thankfully absent, odd tokenizing of the rest of the world shows his fingerprints. Patty Jenkins loves to fly (as she showed in punching her ejector seat straight to Disney), but did we need to lasso so much lightning? (Also, wait, can Wonder Woman fly now? This is still unclear.) While Gal Gadot is definitely a presence and the only person who should be playing Wonder Woman, I can’t tell what films Kristin Wiig and Pedro Pascal are in.

Overstuffed and exhausting, Wonder Woman 1984 is one long tonal whiplash (…lasso-lash?). Littered with Looney Tunes cartoon violence and the unfortunate detritus of yet another ’80s homage (luckily a longstanding diet of Stranger Things has primed younger audiences to navigate its many pop peculiarities so we don’t have to spend too much time on them), the moral of this narrative is ultimately cloudy. While parents will try to impart the ten-dollar word “empathy” onto their kids, they’re too busying ooh-ing and aah-ing over the logic of unlimited wishes to care. I guess smashing these two concepts together doesn’t make for compelling action figure toys we can sell.

Ultimately this is a puzzle I cannot spend more time deciphering. Tired and lazy, I’ve just begun sharing the following video to equally confused friends as my capsule review:

Tell all your friends about the boot.

Because making a ranked list is hard, these shortlist candidates are ordered alphabetically.

Macaroon pastels coat every frame of this photoshoot-in-motion. The umpteenth Jane Austen adaptation, Emma. succeeds by sticking to period but modernizing its tone. Unabridged dialogue sings when it’s married to anachronistic comedic timing. More a romp than a deep romance, the source’s costume stuffiness has opportunity to breath when focused on the quivering tics of awkward stately etiquette.

While 2020 has allowed us ample opportunity to examine America’s original sins, First Cow provides a parable to dissect just one of them: capitalism. The addition of milk from the eponymous bovine to the uninitiated, unrefined American Western expanse joins two strangers into a partnernship of cottage biscuit baking, ultimately upending the quiet outpost’s Eden.

With some of the warmest moments of friendship and the most delicious-looking food cinematography in any film this year, First Cow is a treat that could just inspire every American to reach out to their neighbor or take up their own self-industry of sourdough production.

Thankfully we got Guy Ritchie back from live-action Disney Hell to thrash around in his familiar R-rated sandbox of British despicables. A fun framing device of Hugh Grant and Charlie Hunnam trading gangster tales over drinks is worthwhile, but some disastrous casting (Matthew McConagughey) and characterization (Henry Golding’s Dry Eye) leave much to be desired.

Yet, this film deserves recognition as Something Noteworthy From 2020 for the simple fact that I spent many hours in vain attempting to find and buy the (bespoke) track suits Colin Farrell and his gang of misfits don.

Confined to the windows and time limit of a 50-minute, free-trial Zoom call, Host is the perfect time capsule from the days of Early Lockdown. The visual hallmarks and behaviors of the virtual happy hour meet the horror tropes of a séance turned sour, as peering into the backgrounds of people on the call turns from friendly voyeurism to abject terror. While our embrace of fully attentive, camera-on video calls has waned, Host may not represent any harbinger for the future of horror, but its entire conception, shoot, and release within quarantine is a testament to the creativity this time of isolation has inspired. Just remember—hey, hey, hood on, you’re mic’s off. You’re on mute—no one can hear you scream.

If ignorant to the history of military violence against indigenous populations in Guatemala, this reimagining of the La Llorona folktale offers a very convenient on-ramp to join its slipstream.

After a general on trial for genocide is acquitted in court, he retreats home to his compound. Abandoned by the house staff (a nod to The Exterminating Angel and a universal warning that stuff is about to go bump in the night) and surrounded only by dwindling loyalists, the stage is set to send in our beloved avenging ghost.

Significantly though, while the expected trappings of a haunting set in, they’re buttressed by the protest of common citizens outside the wall. What was that noise down the hall? Was is a spirit waiting for a jump scare? Or another rock thrown over the wall by a furious citizen? With the civil unrest seemingly fueling this spirit demanding government accountability, there comes the epipiany, “Oh, this is very 2020.”

While the end result may not satisfactorily land for mainstream American horror palettes expecting more shrieks, La Llorna leaves a lingering after-image of the horrors we know exist but often feel too underwater to combat.

Written, directed, produced, and edited by its star, Isabel Sandoval, Lingua Franca is a clear, full-throated declaration of a single vision. At its core is an effective study about belonging and struggling to follow best-laid plans, but where the film excels is its ability to contextualize the story within the bigger patchwork of New York City.

The most intimate, interior moments here are captured in extreme wide shots with a telephoto lens, grounding them within the real world of a busy city unfolding around them. It’s a touch that brings to the mind the Safdie Brothers, seizing every opportunity to make a film teeming with claustrophobic and unrefined (aesthetically and socially) life.

It’s inspired filmmaking, a reminder that everyone, every place has a story. It’s just a question of when you start and stop observing each slice of life. It’s the New York City I miss bumping into on the subway.

Its title is seemingly missing a mocking, shouted exclamation mark for a punchline. A serious biography of a person very few today were pining for. So, how to make it matter?

Although billed as a companion piece to Citizen Kane, Fincher does more than a paint-by-numbers retelling of the screenplay’s writing. The lauded film at its center is Mank’s Rosebud, one that flits in and out of the main narrative, but serves as a straightfoward symbol for how an author’s life reflects in art. But Mank wakes up and the ideas start flowing when it explores the seemingly unrelated corners of that life. A cacophony of typewriter dings accompanies identifying a germ of intolerance in our history.

This is a profile of the moment American exceptionalism in storytelling corrupted into something more subtly exploitative and manipulative. The dastardly duo of Louis B. Mayer and William Randolph Hearst are perfect ciphers for the modern-day veneer-shining Forbes cover photos who can put on some semblance of humanity while grinding the common man into a pulp just to fuel their fiction and sense of self grandeur.

The Nest deserves a much more descriptive poster to advertise what it’s really about. Big, bold letters: “2020. Blockbusters Run Scared. This Is The Heavyweight Bout of the Year.” Below, Jude Law nervously adjusting his blazer sleeves. Counter, Carrie Coon gripping both components of a corded phone with enough force to fracture the plastic. Below: “Live From An Isolated Palatial Estate” with pop-out bubbles: “A Marriage in Slow-Motion Destruction!” and “’80s Yuppies Have It All!” Newspaper columnist excerpt at the bottom (in smaller type): “The director of this bout will raise its temperature to boiling point. Sure to be a gem resembling horror more than any familial drama.”

The apple doesn’t fall far from the family directorial tree as Brandon Cronenberg proves with Possessor. And while the science fiction trappings may prove ultimately shallow and remind us of some existing short story work, there’s still much here to applaud.

From the precipice of a Toronto shot so queasily it resembles more a foreign planet, we’re off-balance for what’s to come. There’s a stillness to the transformations and grotesque violence that flare up throughout. With just a few analogue effects shots, we’re given a glimmer of hope that body horror can still terrify, all while touching upon salient themes of fidelity and honesty.

A visually inventive meander through one man’s life, Soul has a lot of big thoughts without concerning itself too much about making any definitive points.

While I tire of the trend of animated films’ insistence of visualizing abstract, ephemeral concepts as navigable, pearly-white operating systems, thankfully Soul doesn’t spend all of its time on an astral journey through such a liminal space.

Whenever we’re treated to life on Earth, it’s vibrant and exciting. Touch and smell are brought to life. City streets swerve into blurs of speeding bodies and cars. Jazz sequences pop with energy. It’s a world with depth, shown especially when 2D-inspired characters dance along its contours, bouncing from pedestrian walk signs to De Stijl advertisements.

Its message about passion and purpose may get muddy, and its ending may seem abrupt, but maybe that’s all in pursuit of being true to life. All we can really hope for from any film is that a spark of excitement or existential reflection will fall out. I don’t know, let’s just say it’s jazzing its way to imparting some wisdom upon you. Suffice to say, kids will hate it.

The actors who defined their films, made bad material great, and occasionally made you crawl the end credits just to see who that was, listed alphabetically.

Cut off from the outside world and every move dictated, a woman commits insubordination by manipulating the only thing she still has power over: the interior of her own body.

Leaning into her typecasting as the oft-forlorn, ignored wife, Haley Bennett shines, embracing camp, but never committing to its humor. A mediation on the line between public and private, Swallow is an exciting exploration into the untapped psychological thriller potential of “pica”, the desire to consume inedible objects.

Some added Technicolor-era grading to channel the vibe of a bored ’50s housewife helps this one go down easy.

Just out of frame: the film’s monster, a stand-in for the real-life disgraced movie producer who doesn’t deserve to have his name capitalized in text.

But by only dissecting the crushing routine of a menial worker under the florescent lights of this anonymous film production company, we’re given more insight into the rippling effects abuse and criminality can have on everyone. Barks and sneering asides are muffled by closed doors and further obfuscated by the soundtrack of copy machines collating and side salad containers popping off. This is the terror of business as usual.

By unfolding over the course of a single day, there’s expectation that Something Might Happen, but nope. The truth is always just out of reach for someone who’s not paid enough to have a voice anyone will listen to. Instead, the same horrors will probably await tomorrow. It’s almost enough of a cautionary tale for all of us to never step foot in an office ever again.

If the emotional ellipsis at the end of Lost In Translation helped define its legacy, then the harder edge of its spiritual successor, On The Rocks was never going to satisfy everyone. Yes, it’s another story from a privileged woman who tells stories (primarily) about privileged women, but here the boredom and ennui that purposefully permeates Sofia Coppola’s work meets aged wisdom in the form of Rashida Jones’s character. All that time pondering has pushed her into asking pointed questions and meting out actual truths.

There’s echos of Coppola’s earlier work, but there’s also a great meta-layering of several stories all syncopating together. A mirrored shot of two generations of fathers playing with children on floors (as if that’s an indicator of patriarchal fealty) drives the paranoia at the center of the narrative forward, but it also serves as a window into the lives of Coppola and Jones, both women who’ve faced uncertainty on how to define their lives as distinct and separate from their accomplished (and flawed) fathers.

Read as a purposeful statement to them, but also as a repudiation of Murray’s lovable (but actually loathsome) Lost in Translation character, the film’s climax of dressing down the aged playboy archetype is extremely meaningful. All those years jestering in infidelity has left him running on fumes, alone and far away from any semblance of a normal nuclear family. To see the clownish Murray cry is a clarion call to finding meaning and purpose in what’s in front of you. Slow, egotistical, and melodramatic, this is an endorsement for messy but gorgeous-looking personal breakthroughs.

The brilliance of Driveways lies in ping-ponging between generations’ perspectives, deftly balancing a child’s outsider status with an old man’s adopted one. In the middle, Hong Chao’s character recognizes both, a pull towards and an anxiety of being a part of something apart of yourself.

It’s a three-pronged character study that doesn’t feel like work because it feels so recognizable. The small-scale scenarios are true-to-life, occasional moments we would never ask to be a part of but inevitably must all endure: the awkward adolescent playdate with neighborhood kids who have nothing more in common than proximity, the geriatric calcification of routine, and the quiet claustrophobia of deciding your place in life.

Life’s path may not be as straight as a driveway, but no matter where the road beyond takes us, if it at least features a single halcyon birthday party with bingo, then we know we’ve some great decisions.

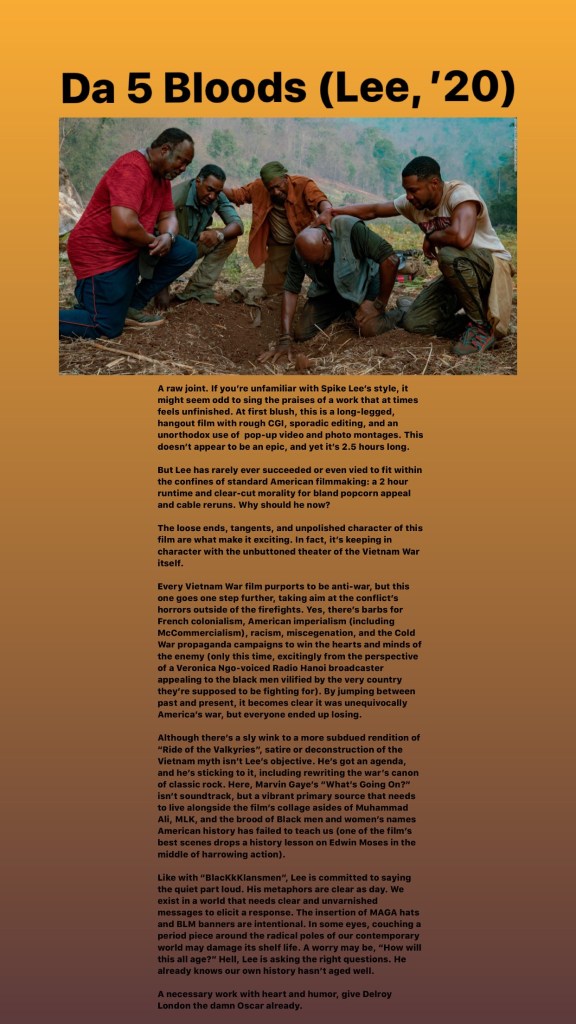

A raw joint. If you’re unfamiliar with Spike Lee’s style, it might seem odd to sing the praises of a work that, at times, feels unfinished. At first blush, this is a long-legged, hangout film with rough CGI, sporadic editing, and an unorthodox use of pop-up video and photo montages. But its loose ends, tangents, and unpolished character are what make it exciting. In fact, it’s keeping in character with the unbuttoned theater of the Vietnam War itself.

Every Vietnam War film purports to be anti-war, but this one goes one step further, taking aim at the conflict’s horrors outside of the firefights. Yes, there’s barbs for French colonialism, American imperialism (including the McDonald’s variety), racism, miscegenation, and the Cold War propaganda campaigns to win the hearts and minds of the enemy (only this time, excitingly from the perspective of a Veronica-Ngo-voiced Radio Hanoi broadcaster appealing to the Black men vilified by the very country they’re supposed to be fighting for). By jumping between past and present, it becomes clear it was unequivocally America’s war, but everyone ended up losing.

Although there’s a sly wink to a more subdued rendition of “Ride of the Valkyries”, satire of deconstruction of the Vietnam myth isn’t Lee’s objective. He’s got an agenda, and he’s sticking to it, including rewriting the war’s canon of classic rock. Here, Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” isn’t soundtrack, but a vibrant primary source that needs to live alongside the film’s video collage of Muhammad Ali, MLK, and the brood of Black men and women’s names American history has failed to teach us. (One of the film’s best scenes drops a history lesson on Edwin Moses in the middle of harrowing action.)

Like with BlacKkKlansmen, Lee is committed to saying the quiet part loud. His metaphors are clear as day. We exist in a world that needs unequivocal messages to elicit a response. The insertion of MAGA hats and BLM banners are intentional. In some eyes, couching a period piece around the radical poles of our contemporary world may damage its shelf life. A worry may be, “How will this all age?” Hell, Lee doesn’t care. He already knows our own history hasn’t aged well.

Four teens meet at their parents’ respective funerals, run away from society, and form a band. With no-future nihilism as its apparent mission statement, on paper this appears to be a digital update of Trainspotting (there’s even a nod to aimlessly wandering through a picturesque field just to have an emotional breakdown).

But when the film’s initial wake involves slapstick, you know you’re in for a more slippery uphill trek to catharsis. Death is the perfect blank canvas for emo and punk aesthetics, deployed here to create a hyperkinetic, vibrant, loud, and funny bloodletting to being lonely and finding your tribe. Rife with tangents (or side quests), the video game logic on hand puts Edgar Wright to shame and the Michel Gondry-inspired crappy crafting unpolishes the film’s edges and gives the genre of tragi-comedy new life.

“I guess that’s what a man does” are words uttered by an otherwise insignificant character in this film but come to define the drive of Steven Yuen’s patriarch for most of its run time. A deft dissection of masculinity the family dynamic, Minari wants you to think with your heart.

Sure, it’s a movie about making it in America, but there’s no major arguments within the family about assimilation or keeping intact what’s Korean about themselves. The conflict front and center is always elemental and substantive. Can we survive? Can we afford this? Can we build something for themselves? Can we have a future here?

When the answers formulate, it’s never in betrayal of the characters’ motivations. In another way, salvation comes when the family stops trying to act how they imagine a family should be and embraces what it already is.

Possessing the most encyclopedic reservoir of film references, Steven Soderbergh mixes and matches to create a sly screwball comedy that also knows when to give a wink to comedy of errors.

Adding to the humor is a self-aware irony that makes this film look more important than how superfluous it really is. The warm, tungsten glow that bathes Let Them All Talk recalls the exotic, globetrotting fun of Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Trilogy, Contagion, and Haywire, all while moored to little more than a slow, geriatric cruise (nay–“crossing”). Along with an insistence on editing conversations to focus on listeners’ faces, instead of dramatic moments, we’re treated to waves of cringe, like when a gulp of water at a dinner table attempts to hide a nervous tic.

The cherry on top is that Meryl Streep’s author character is almost relegated to a supporting role, hermitting away in her room to work on a manuscript. As if the rest of the characters were awaiting for the famed star to emerge from her trailer to being shooting, the asinine activities her satellite friends, family, and acquaintances partake in to bide time really fuel the mood and the narrative.

Filled with the purest earned laughs in any film I saw this year, Let Them All Talk proves that Soderbergh can still create light, breezy fun while still challenging himself to shoot an entire film in a single transatlantic nautical voyage.

Steve McQueen’s films–and artwork–put emphasis on how objects and bodies fill familiar spaces. A colander continuously rocking on a recently vacated kitchen floor can better speak to the echoes of police violence in a community than a split-second truncheon strike.

When bodies slide in, power structures play out. There’s an incongruity to how nine people could be crammed into a single defendant’s box for a fair, impartial trial. When visualized, there’s an elementary fault to how four officers could simultaneously peer through a police investigation van’s eyehole slit. As images, McQueen uses these bodies to portray alienation and the precarious grasp of hegemony.

As laid out by one of the film’s legal defendants, Small Axe: Mangrove is a court case whose guilty-not guilty verdict isn’t the end result. This is about building an argument up with such overwhelming evidence that it can begin to pick apart an entire entrenched system and change a conversation on the whole. Like those aforementioned bodies, it’s about breaking out of a box and creating an entirely new one.

I had a teacher in high school who maintained that the ideal novel’s structure mirrors that of a baseball game. You start at home, you experience an inciting event to embark on a journey, encounter threats and challenges moving between safe havens, and eventually return home after acquiring an experience or reward. Nomadland follows this path.

The film’s opening card lays out how society has literally left Frances McDormand’s character behind through the line-item deletion of an entire zip code. From this, an anti-establishment pioneering spirit is lit and burns like wildfire throughout, spanning states and seasons. And although transient, she is grounded by fleeting but deeply sincere personal relationships. It’s her fellow travelers, many real people who’ve been living this lifestyle that fill in the film’s wide margins and help remind her of its cyclical nature. We can always return to something familiar further down the road.

More than a simple travelogue, Nomadland is a day-to-day catalogue of resilience that you may not recognize but would be hard-bent to deny feels fully American–in all its dim and twilight glory.

The Truth / Deerskin / The Whistlers / Les Miserables / The Gentlemen / Olympic Dreams / The Assistant / Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn) / The Lodge / To All the Boys: Always and Forever, Lara Jean / Sonic the Hedgehog / Downhill / Greed / Emma. / The Invisible Man / Never Rarely Sometimes Always / The Hunt / Blow the Man Down / Big Time Adolescence / The Way Back / The Wild Goose Lake / Bacurau / Onward / Tigertail / Arkansas / The Half of It / Extraction / Like a Boss / The Wrong Missy / John Henry / Buffaloed / dd Selah and the Spades / The Lovebirds / Da 5 Bloods / The King of Staten Island / The Vast of Night / The Rental / Artemis Fowl / Good Boy / 7500 / My Spy / The Outpost /Shirley / We Are Little Zombies / Palm Springs / The Old Guard / Greyhound / Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga / I’m No Longer Here / Driveways / Bad Boys for Life / She Dies Tomorrow / Timmy Failure: Mistakes Were Made / An American Pickle / First Cow / Color Out of Space / Wasp Network / Babysplitters / Tommaso / The Trip to Greece / Cut Throat City / The New Mutants / Love, Guaranteed / I’m Thinking of Ending Things / Mulan / Unpregnant / Seberg / The Devil All the Time / Tenet / The Broken Hearts Gallery / Beats / Crazy World / Vivarium / The Binge / Boys State / I Used to Go Here / Cuties / Lingua Franca / Hubie Halloween / Charm City Kings / Enola Holmes / The Trial of the Chicago 7 / David Byrne’s American Utopia / Night of the Kings / Vampires vs. the Bronx / Borat Subsequent Moviefilm / On the Rocks / Yes, God, Yes / The Wolf of Snow Hollow / Bad Hair / Host / La Llorona / Possessor / Antebellum / The Nest / Kajillionaire / The Personal History of David Copperfield / Rebecca / The Boys in the Band / Happiest Season / Bad Education / Underwater / Run / Small Axe: Mangrove / Unhinged / Small Axe: Lovers Rock / Sound of Metal / Small Axe: Red, White and Blue / Black Bear / Farewell Amor / Freaky / Mank / Wander Darkly / Nomadland / I’m Your Woman / His House / Small Axe: Alex Wheatle / Let Them All Talk / Shithouse / One Night in Miami / Lost Girls / Minari / The Stand In / Swallow / Small Axe: Education / Another Round / Wonder Woman 1984 / Soul / Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom / Promising Young Woman / Leap / Sylvie’s Love / Ava / Yellow Rose